Sir David Fletcher Jones (1895-1977), businessman, was born on 14 August 1895 at Bendigo, Victoria, fifth (third surviving) child of Samuel Henry Jones, a blacksmith from Cornwall, and his Victorian-born wife Mahala, née Johns. After Mahala died in 1897, Samuel remarried and had four more children. The families blended happily, and Fletcher recalled his childhood fondly: 'the greatest inheritance is to have been born into a struggling Christian household'.

The Jones family was Labor in politics, Methodist in religion and improving working class in its social aspirations. This background, together with the camaraderie of Cornish mining families and the fellowship of the Methodist congregation at Golden Square, fostered in Fletcher both a desire for individual improvement and the moral imperative to leave the world better off.

In 1908 he left Golden Square State School; he worked for two years in a Bendigo auction-room and then spent three years establishing for his father a tomato-farm on scrubland at Kangaroo Flat. He read omnivorously, and aloud, in an attempt to overcome a bad stammer. Fascinated by tailors' workrooms, he often walked from Kangaroo Flat to Pall Mall, Bendigo, to gaze in their windows.

Enlisting in the Australian Imperial Force on 15 July 1915, Jones sailed to Egypt and in March 1916 was sent to France with the 57th Battalion. He saw action in the battle of Fromelles before being evacuated to England in August with trench fever. Repatriated in 1917, he was discharged medically unfit on 8 February 1918. His stammer had returned, worse than before, but repatriation doctors warned that he would have to 'speak or starve'. Rejecting a war pension, he became a door-to-door salesman in Melbourne's inner suburbs, where poverty and hopelessness prejudiced him for ever against cities. He turned his thoughts to hawking in rural Victoria, of which he and his army cobber Stan Clapton had dreamed in the trenches in France.

In 1918 Jones took a loan from the Repatriation Department, bought a hawker's wagon, stocked the outfit with manchester from Flinders Lane and mapped a circuit in the Western District from Skipton to Terang. Clapton & Jones soon worked up a good trade among shearers, farmers' wives and friendly townsfolk. Offering quality and value, they quickly learned that 'the customer was always right'. When the partnership was dissolved, Jones bought a commercial traveller's drag and initially worked alone, moving into the Otway Ranges and westward into South Australia. Gathering about him a small and loyal staff, he married the flair of the showman to the business of commercial travelling. He bought trucks and trailers, hired shops for three-monthly sales, erected marquees on vacant land, and expanded into tailoring and dressmaking.

On 23 September 1922 at the Methodist Church, Golden Square, Jones married Rena Ellen Jones (d.1970), a friend from childhood, and soon decided to settle down. In 1924 he purchased on credit a menswear and tailoring business at Warrnambool. The poorly chosen site, the town's social conservatism and his rivals' suspicion saw his dignity bruised when he was forced to come to an arrangement with his creditors. Jones was a dedicated reader of American periodicals on modern merchandising techniques. His responses to his precarious business position—daily 'specials', spot sales and competitions—were simple and inexpensive, but attracted the desired attention and custom. Jones's exuberant showmanship spilled over into community activities. He organized Warrnambool's winning entry in the Sun News-Pictorial's 1927 Ideal Town contest, collected and distributed Toc H support for the unemployed during the Depression and ran the highly popular community singing. Above all, he proved astute in business, managing his credit on a knife-edge, buying goods in small quantities and initiating group-buying by tender. He also recruited ambitious salesmen, and skilled tailors discharged by other firms. By 1939 his tailors' room was one of the largest in provincial Victoria and he had repaid his Melbourne creditors in full.

The year 1941, when he decided to make nothing but trousers, marked a turning-point. The Commonwealth Department of Supply awarded him a contract for army pants and Fletcher Jones rapidly made a reputation for hard-wearing, 'coverdine' work trousers, particularly among men on the land. By 1945 his Warrnambool rooms were supplying 123 retailers in four States. Offended by their indifference to the principle of fractional sizes, he decided to sell directly, to insist on personal fittings and to accept cash only. The response, from Australians chafing from continuing austerity, was astonishing. Customers besieged his first shop when it opened in Collins Street, Melbourne, on 23 June 1946. Queues stretched for blocks under signs proclaiming 'Fletcher Jones of Warrnambool—nothing but trousers. 72 scientific sizes. No man is hard to fit'.

Jones had long been fascinated by American industrial efficiency. A subscriber (from 1922) to Herbert Casson's Efficiency Magazine, he was acquainted with the ideas of Henry Ford, Andrew Carnegie, Frederick Taylor and Lillian Gilbreth. The traditional methods which dominated tailoring left him frustrated, not only with the time-wasting but with the depressed nature of the craft and worker exploitation. Yet, he distrusted schemes which encouraged a spurious identification between worker and business, and which seemed designed merely to extract more labour without increasing job satisfaction. Spiritual growth, he believed, was achieved through productive and satisfying work, and the object of business should be social advance rather than individual profit.

Wondering during the depths of the Depression 'why the rich were getting richer and the poor poorer', he read (with self-confessed difficulty) analyses of capitalism by Victor Gollancz, Harold Laski, J. B. S. Haldane and the Webbs, and studied the history of the co-operative movement. Fabian socialism, being eclectic and pragmatic, appealed to him. He became acquainted, too, with the work and writings of the Japanese Christian pacifist and socialist Toyohiko Kagawa, who succoured the homeless of Tokyo's slums and pioneered consumers' and farmers' co-operatives and student credit-unions. Jones arranged for Kagawa to speak at Warrnambool during his 1935 Australian visit; in 1936 he visited Kagawa's Japanese co-operatives. He was influenced by Kagawa's Brotherhood Economics (1937) and that year issued his own statement, 'Co-op Pie'.Supported by his wife, he began from the late 1940s to turn his business into a co-operative, the name Fletcher Jones & Staff Pty Ltd first being used in 1947 for a company to replace the Man's Shop of Fletcher Jones Trousers Pty Ltd in Melbourne. The basic objectives included commitments to raising the quality of Australian-made clothing, to bringing made-to-measure garments within the reach of the ordinary man, and to revolutionizing the firm's management and ownership in line with consultative and co-operative principles.

In 1947 Jones visited England and the United States of America to inspect the latest production methods. What he saw of repetitious operations reinforced his earlier reading and convictions about efficiency. Within a year the firm began a major expansion, buying—as the new factory site on the outskirts of Warrnambool—a rubbish dump in a former quarry, and determining to transform it from an eyesore into a showplace. Disparaged at the outset as a 'shanty town' collection, the factory in a landscaped garden-setting at Pleasant Hill became a tourist mecca by the 1950s.

The 1950s and 1960s saw an expanding range of Fletcher Jones services and products, notably an extension of the range of garment fabrics, the provision of an after-sales cleaning and repair service on a non-profit basis, and the decision in 1956 to make women's skirts and slacks, the last a result of winning the contract to outfit the Australian Olympic team. The company remained at the cutting-edge of industrial innovation, introducing methods-engineering practices (1954), the Australian clothing industry's first textile testing laboratory (1964) and computerized tailoring systems (1974). When in 1966 the company decided to make suits, it found that it had exhausted Warrnambool's supply of skilled labour and had to open in the Melbourne suburb of Brunswick. But Warrnambool remained the administrative centre, production base and social heart of the 'FJ Family'. The original plan for the co-operative envisaged the Jones family retaining a two-thirds interest and the staff one-third, but Fletcher surrendered his interest so readily that the staff held 53 per cent of the shares by the early 1950s and over 70 per cent by the 1970s. At Scots Memorial Church, Surfers Paradise, Queensland, on 5 October 1971 he married with Presbyterian forms Aida Margaret Wells, née Pettigrove, a 66-year-old widow.

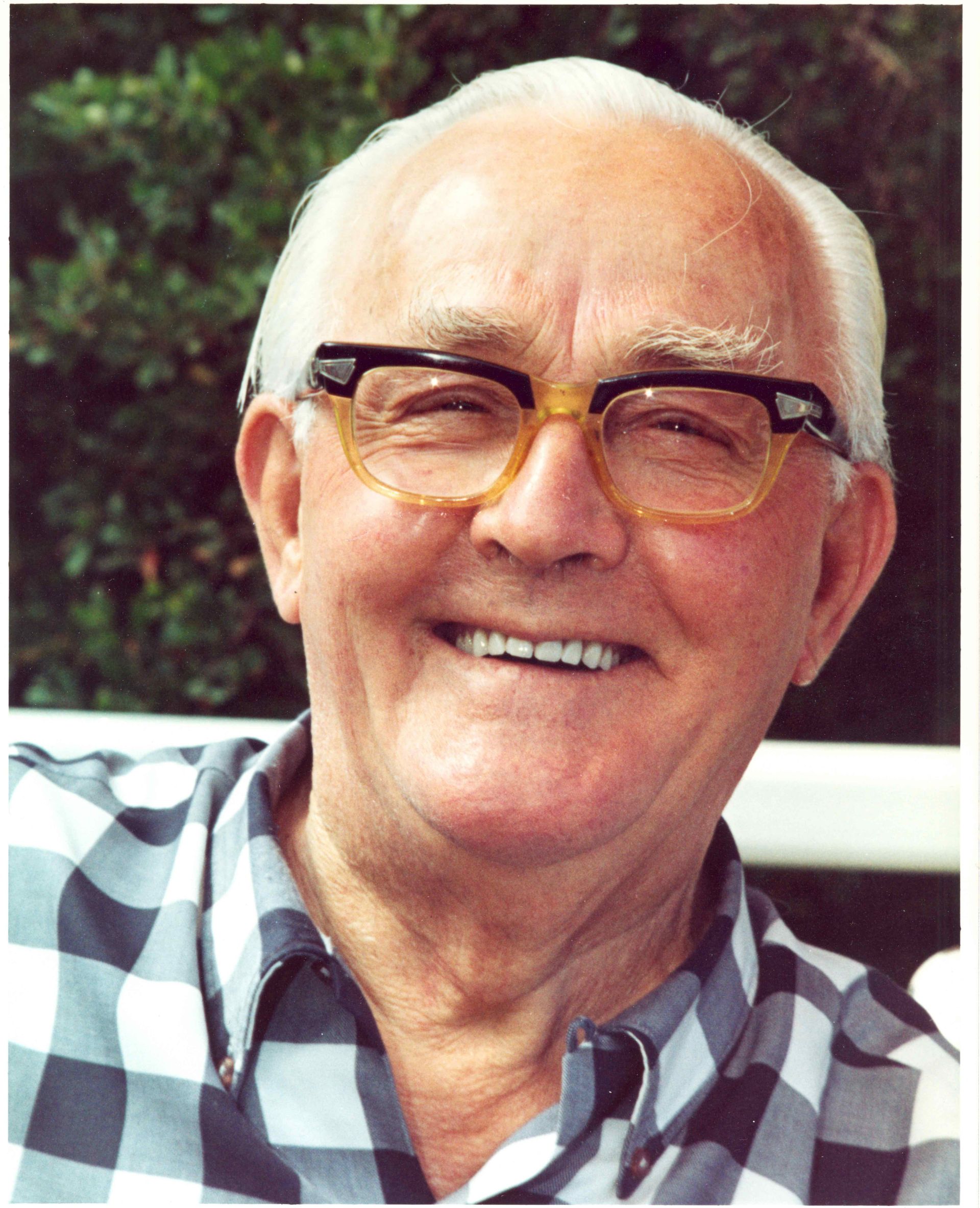

Jones was widely admired. In manner he was gregarious and affable, and given to aphorisms; in appearance, he was a trim and neat 5 ft 9 ins (175 cm), impeccably groomed, a non-smoker and teetotaller. His other business activities included chairmanships of Warrnambool Woollen Mill Ltd (1943-58) and of Hanro Ltd (1959-63), and membership of the Victorian Promotion Committee (1962-75). He lived simply, in a two-bedroom bungalow near Pleasant Hill, and drove a 1962 Rover 2000. Warrnambool named him citizen of the year in 1958. He was appointed O.B.E. in 1959, and knighted in 1974 for services to decentralization and the community, an honour long delayed by the Liberal era, it was thought, because of his clear Labor sympathies and his alternative business practices. Reports of the Whitlams' agnosticism, however, caused him publicly to renounce his political allegiance.

Sir Fletcher remained chairman of Fletcher Jones & Staff Pty Ltd and governing director of the holding company, Fletcher Jones Organizations Pty Ltd, until 1975 when failing health forced some reduction of his direct responsibilities. Reviewing his career in 1974, he said, 'I had no vision or grand dream. Trading was in my blood and I wanted to be good at it . . . that was all'. His memoir, Not By Myself (1976), bound in imitation coverdine, acknowledged the vital contribution from friends and well-wishers, some of them total strangers, whose goodwill had sustained his confidence, strengthened his Christian faith and confirmed his belief that religion could be expressed in business life. Symbols of an affluent and self-confident postwar nation, the man and his firm were celebrated for their material success, but in fact embodied a genuine and challenging expression of an Australian egalitarianism informed by Christian teachings.

Survived by his wife, and by the daughter and two sons of his first marriage, Jones died on 22 February 1977 at Warrnambool and was buried in the local cemetery. His estate was sworn for probate at $326,795. At that time his enterprise was one of the largest clothing manufacturers in the world, with almost three thousand employed in four factories and in thirty-three stores through every Australian capital city. Arguably, no single person or firm had done more to transform and, for a time, homogenize Australian dress standards, particularly among men, than Fletcher Jones and his staff.

John Lack Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 14, (MUP), 1996